In Memoriam: Gwynn, Zimmer, Kiner Among Notable Sports Deaths In 2014

NEW YORK (CBSNewYork/AP) -- For one, the tool of choice was a bat. For the other, a stick.

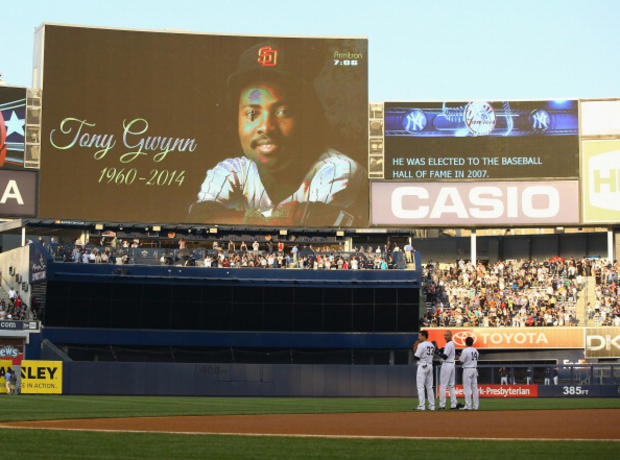

Tony Gwynn and Jean Beliveau died in 2014, unparalleled craftsmen who made the supremely difficult look almost easy.

They played with elegance and grace, ambassadors for baseball and hockey. They were enduring landmarks in their cities — Gwynn in San Diego, Beliveau in Montreal. They were sports royalty, yet never lost the common touch.

Dodgers broadcasters Vin Scully called Gwynn a "genius with the bat." Who could doubt that? With a left-handed swing as fluid as any in the game, Gwynn owned the real estate between shortstop and third base, unerringly slashing singles through the left side.

He won eight batting titles and finished with a .338 career average, rarely striking out. He did not hit below .309 in a full season. He played in two World Series, and hit .371 while he was there. In 1994, he neared baseball's Holy Grail of .400, only to be stopped by a players' strike and ending at .394. By the time he quit in 2001, he had 3,141 hits.

Fellow Hall of Famers understood the level of excellence. Ryne Sandberg made it a point to watch Gwynn take batting practice. Greg Maddux called him the "best pure hitter I ever faced."

Gwynn spent all of his 20 years in San Diego, where he was "Mr. Padre," his diligence and study of the game unsurpassed. He happily talked at length to rookies about the art of hitting, his laughter cackling across the seasons. He died at 54 and believed his years chewing tobacco had much to do with his oral cancer.

"The greatest Padre ever," Commissioner Bud Selig said, "and one of the most accomplished hitters that our game has known."

Beliveau, like Gwynn, played all 20 years for one team. He might have been the most revered of all the Canadiens, and in Montreal that is no small thing.

As Gwynn had great vision on the diamond, so it was with Beliveau on the ice. He combined strength and delicacy at center and for a stretch in the mid-1950s he led Montreal to five straight NHL titles, the bedrock of a dynasty.

He finished with 507 goals when he retired in 1971. A year later, the normal wait dispensed with, he entered the Hockey Hall of Fame. In all, he won 10 Stanley Cups and was twice the MVP. There were seven other titles as a Canadiens executive.

"It was such a pleasure to watch him play and handle the puck, teammate Donnie Marshall said. "He was so graceful on the ice."

Beliveau, Montreal's captain, was the quintessential gentleman. He died at 83 and his funeral had the trappings of a state affair. Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper was on hand. Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard said Beliveau was the "image of what we would like ourselves to be."

Ken Dryden, Montreal's longtime stellar goaltender, said his one-time roommate made every occasion better.

"He said the right things, in the right way, in French and English," Dryden recalled. "Because that's what he believed and that's what he was."

Other deaths this year, lives that illuminated sports:

RALPH KINER, 91: Generations of fans came and went who knew of Ralph Kiner only from the broadcast booth. He was the announcer who was there right from the start with the Mets, stayed in living rooms for a half century and sometimes confronted the English language like an infielder flailing at a windblown pop. But, boy, could this guy hit. He joined the Pirates after World II and finished with 369 homers, sixth on the career list when he retired. For a decade, nobody belted the ball like this Hall of Famer. In his first seven seasons, he won or tied for the NL lead in home runs. Left field at old Forbes Field was Kiner's corner. Said Hall of Fame President Jeff Idelson: "Ralph struck fear into the hearts of the best pitchers of baseball's Golden Era."

DON ZIMMER, 83: A popular fixture in professional baseball for 66 years as a manager, player, coach and executive, Zimmer was still working for the Tampa Bay Rays as a senior adviser. Zimmer started as a minor league infielder in 1949. He played for the only Brooklyn Dodgers team to win the World Series, played for the original New York Mets, nearly managed the Boston Red Sox to a championship in the 1970s and was Joe Torre's right-hand man with the New York Yankees' most recent dynasty. "I hired him as a coach, and he became like a family member to me. He has certainly been a terrific credit to the game," Torre said. "The game was his life. And his passing is going to create a void in my life … We loved him."

FRANK CASHEN, 88: The general manager who wore a signature bow tie and fashioned a Mets team that rollicked its way to the 1986 World Series championship. Cashen was a longtime sports writer in his Baltimore hometown before joining the Orioles and eventually becoming their GM. The Orioles won two titles while Cashen worked for them. "He was a man of integrity and honestly, and that was most important. He told you the truth," former Mets first baseman Keith Hernandez said. "It was a day when the general managers didn't pal around with the players. We hardly ever saw him, but there was a relationship there. He was just a wonderful man."

RUBIN "HURRICANE" CARTER, 76: Bob Dylan sang about him: "Here comes the story of the Hurricane/The man the authorities came to blame/For something that he never done." Denzel Washington starred in a movie about him. Rubin Carter was never a champion, but he could throw hurricane waves of punches. And his shaved head — not quite the fashion statement then — lent an unmistakable air of menace, as did a criminal past before his turn to boxing. In 1963, he stopped Emile Griffith in the first round and a middleweight title seemed within reach. Then came his murder conviction for three deaths in 1966 in a New Jersey bar. He was convicted again 1976 and freed in 1985, the judge saying the case had been "predicated upon an appeal to racism rather than reason." He spent 19 years in prison, a symbol of justice denied and the law's delay. He resettled in Canada and advocated for those wrongly convicted. He did not let anger consume him. "He kind of got above it all," friend Thom Kidrin said. "That was his great strength."

CHUCK NOLL, 82: Summon fierce names from football lore like Joe Greene, Jack Ham, Jack Lambert and Franco Harris and then throw in the likes of Terry Bradshaw, Lynn Swann and John Stallworth. They were products of Chuck Noll, a coach who won a record four Super Bowls and reshaped the Pittsburgh Steelers from woebegone franchise to one as durable and unyielding as its nickname would suggest. He coached for 23 seasons and until he came aboard the Steelers had never won a playoff game. But in the 1970s, no one was like them. He went 16-8 in the playoffs. The "Steel Curtain" and the "Immaculate Reception" came on his watch. Demanding and confident, Noll kept his distance from his players. He was always the steady hand. Steelers owner Dan Rooney got to the core of it: "He was one of the great coaches of the game."

JACK RAMSAY, 89: Dr. Jack he was called, and the honorific was legit — a doctorate in education from the University of Pennsylvania. Jack Ramsay was the consummate student and instructor of the game. He cut his teeth in coaching at St. Joseph's and then had NBA stints in Philadelphia and Buffalo before landing in Portland. His championship season was 1976-77 — his first with the Trail Blazers - where the game was played with a crispness and intelligence as in few other places. The quality of the basketball better reflected the man than his taste in sports jackets. Bill Walton and Maurice Lucas were Ramsay's pillars. He would coach 21 seasons, never reaching the summit again. He called it "a once-in-a-lifetime experience." He brought his coaching savvy to broadcasting. And all the while he kept running and swimming, even when the body began to fail, always in motion. "He left an indelible mark on every facet of our game," NBA Commissioner Adam Silver said.

RALPH WILSON, 95: He started in the insurance business but would plunk his cash in a venture called the American Football League. He was ridiculed for throwing away good money. Ralph Wilson would go on to become the Buffalo Bills' only owner and a cornerstone of the modern NFL. His team was an anchor in western New York. It won two AFL titles in the 1960s and made it to four straight Super Bowls, only to lose every one. The string of defeats never cost him his sense of humor, and he always had his players' backs. The late Raiders owner Al Davis called him the "conscience" of the league. Wilson was the last surviving AFL founder. Said Bills Hall of Fame coach Marv Levy: "He meant so much to the game . and to the community of Buffalo and beyond."

LOUIS ZAMPERINI, 97: He finished eighth in the 5,000 meters at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Still, Adolf Hitler was impressed with the last-lap kick by this California teenager. Louis Zamperini's tale was first beginning. As a World War II bomber pilot, he was shot down in the Pacific. He spent 47 days on a raft in shark-infested waters and given up for dead back home. He drank when it rained, ate by catching birds and fish with his hands. His rescue came by way of capture by the Japanese, who imprisoned, beat and tortured him. He credited sports — boxing as a boy to deal with bullies, later the discipline of running - with his survival. "Pain never bothered me," he once told the AP. "Destroying my dignity stuck with me." Many years later, he wrote a letter forgiving one of his most merciless prison guards. At the 1998 Nagano Olympics, he ran in the torch relay past where he was jailed. His life is chronicled in the just-released movie "Unbroken," based on the best-selling book. "Of the myriad gifts he left us," Laura Hillenbrand, author of the biography said, "the greatest is the lesson of forgiveness."

ERNIE VANDEWEGHE, 86: New York Knicks player in the post-World War II era and father of former NBA star Kiki Vandeweghe and three other top athletes. Vandeweghe, who played 13 seasons in the NBA, averaged 9.5 points and 4.6 rebounds in 224 regular-season games for the Knicks from 1949-56. In college, he averaged 19.1 points in four seasons at Colgate. He was chairman of the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports and served on the Olympic Sports Commission.

ALVIN DARK, 92: Player and manager on World Series champions. Dark was the 1948 Rookie of the Year and a three-time All-Star shortstop. He played alongside Willie Mays when the New York Giants won the 1954 title, and he guided Reggie Jackson and the Oakland Athletics to the 1974 crown. Dark hit .289 with 126 home runs in 14 seasons with the Braves, Giants, St. Louis, Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia. In 1961, Dark began a managing career that spanned 13 seasons in which he went 994-954 with the Giants, Kansas City and Oakland A's, Cleveland and San Diego.

You May Also Be Interested In These Stories

(TM and © Copyright 2014 CBS Radio Inc. and its relevant subsidiaries. CBS RADIO and EYE Logo TM and Copyright 2014 CBS Broadcasting Inc. Used under license. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed. The Associated Press contributed to this report.)