Keidel: Football's Junior And My Senior

By Jason Keidel

» More Columns

When my father turned 32, his mother shot herself in the head.

I'll never forget waking up on that morning, scooping the crust from my eyes as I made my morning jaunt to the living room for a round of cartoons. I paused by their bedroom door to wish my Dad Happy Birthday and saw him slouched on the bed, my mother's right arm lapped around his waist, while he cried, his broad shoulders bouncing with each breath. It was the first time I ever saw him cry.

Somehow, I knew not to inquire. I was six years old.

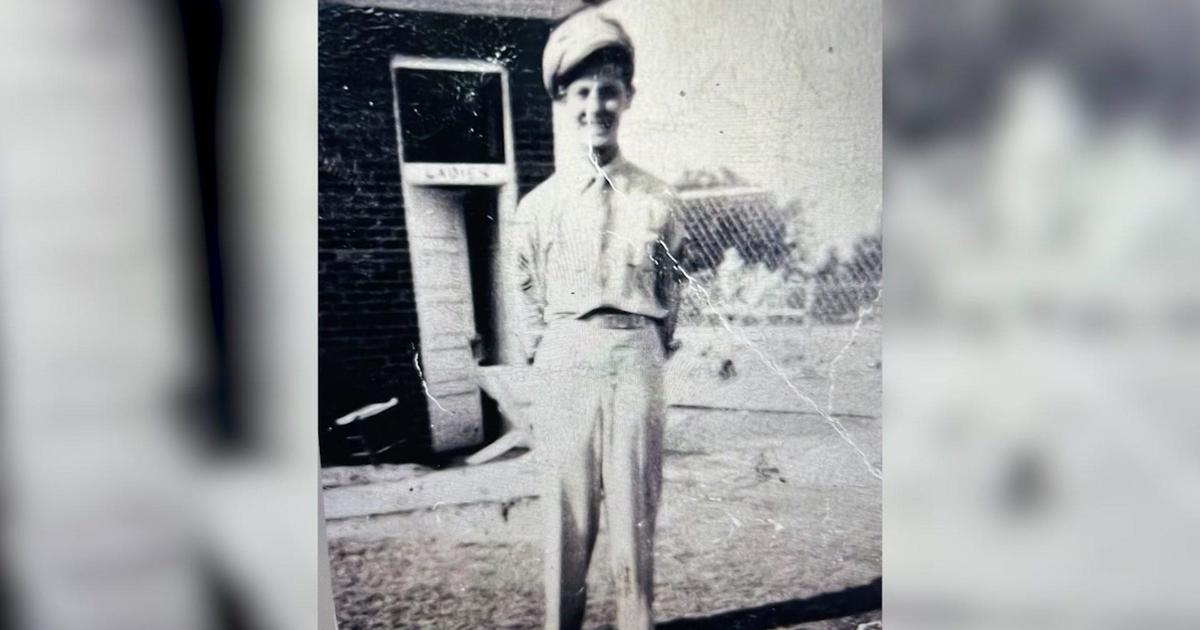

It was the last in a series of satanic birthday presents she gave my old man. She abandoned him when he was born, literally dropping him at his grandmother's doorstep. He spent a little time with her as a teen, and she was true to her vulgar narrative, telling my dad he was as worthless as his dad: brawny, brainless and hopeless.

We know that the bulk of abusers, verbal or physical, were also abused as kids. But rather than stretch the cycle of baleful neglect, my Dad made sure I had all the things he didn't – most notably, love. He never missed an Astros football game in Van Cortland Park, a high school basketball game in Manhattan, or a distant cry when I broke a bone on the concrete playgrounds of NYC.

From 1969 until 1989, my father was a man on a mission. And that mission was to love his son for the first 20 years of his life. He loved me more than he loved any woman, any thing, or any idea. His body was little more than a vessel, a vanguard of fatherhood. We were so close it felt like we shared one heart. We certainly shared more than DNA.

But eventually, the memories, the aggregate agony of such a foul childhood began to creep back up in his life, like a dormant disease out of remission, slowly swallowing his soul. As an adult I'd come visit him in the apartment where he raised me, on 97th & Columbus Ave. I'd see him on the couch, his endlessly long legs stretched to the other end, his face under a cone of lamplight, reading a book, a glass of Scotch on his left, with the cubes twinkling and popping in the warm whiskey…

…and a .357 magnum laid flat on the edge of the glass table, also glinting in the dim swath of light. Six bullets stood at attention next to the gun, like vertical coffins, each one bearing his name. He said he kept the gun close by in case of home invasion. In fact, he was contemplating his mother's solution to life. I was too obtuse to see it, because all I knew was the man, the monolith, the Herculean creature who protected me. How can he be sick when he made sure I was healthy?

Though he never pressed the gun to his flesh, he did try to kill himself – twice, both times guzzling pills. His stomach was pumped each time, sparing his life by minutes. When I visited him in the hospital after the second suicide attempt, I told him, "If you try again and fail I'm gonna finish the f@#*ing job for you."

Yet the only man I'm sure has ever loved me is my father, my Dad, my hero. He gave everything he had to me, for me, with me. And he's the only reason I'm alive, the only reason I'm a man. And because his pain became too much to handle you want me to call him selfish? I don't think so.

****

Famed football player Junior Seau committed suicide yesterday. His career speaks for itself, and his place in NFL history is assured. And while you wouldn't be wrong to wonder why it's tragic only when celebrities do it, remember that sports are so intimate with us because they are us.

Sports are only a pretext for social commentary. The only difference between them and us is they are slightly larger and wear uniforms. All the successful life maxims are proper sports mantras, and the reverse – teamwork, sacrifice, hard work, and love – for the game, your team, your town, yourself.

In a few months, Seau will be forgotten, a bookmark in the fading chapters of our sporting memoirs. "That's right," we'll say with sudden sadness when his name pops up in an arbitrary sports chat. "He killed himself."

But his family and friends won't forget. And we should not be so dismissive of someone's pain simply because there isn't a pill for it, because an x-ray can't spot it, because a surgeon can't stitch it. And if you saw Seau's mother beg the camera to take her life and return her son, you realize the transaction of a shotgun blast isn't so simple.

We've seen the montage of memorials to Seau, of tearful testimonials and guilt. "If only I knew," many of them said. Marcellus Wiley was particularly poignant, whispering out words between breaths, hiccups, and tears. It was hard to watch him cry without crying myself. Beyond Seau's transcendent career – 12 Pro Bowls and a clear path to Canton – it seems he was equally admirable off the gridiron. Wiley, Bobby Ross, Dean Spanos, and John Elway (among many others) lauded Seau for his work in the community. His charity reportedly raised over $4 million for children in need.

Shortly after hearing about Seau, I was in my car, listening to the Mets game. During a commercial break, I turned my dial to ESPN Radio, where the host, who also calls Yankees games on television (you can guess his name), suggested that Seau might have been selfish because he pulled the trigger.

That kind of ignorance could be as dangerous as the problem itself. These people don't know Seau. They don't know my Dad.

****

Suicide and suicide attempts are rampant in my family. And no matter how removed we think we are from such thoughts, they do sprout when you're around it so much. Fortunately, my neuroses take on different forms.

But once a year or two, out of nowhere, I think, "Why not? They would be sad for a few weeks and then move on, love and life marching inexorably toward the same place, eventually joining me under a bright, noon sky, on some verdant hill, the tall grass smoothed flat by a noon breeze. Cemeteries are rather appealing from afar, until you know what's under those tombstones that jut like teeth from the dirt. Who would know, really? And, really, who would care? It's gonna happen one day, someday, anyway. My life never turned out the way it should have, the way everyone expected it to…

Thank God for friends and family. Thank God for laughter. Thank God for sports.

My mother attempted suicide a few years after my grandmother succeeded. Pills and Scotch. I was ten, I think, coming home from school when a gurney was being wheeled out of my apartment. One of my neighbors, a saint of a woman named Evelyn, covered my eyes and pulled me into her apartment, telling me it was someone else, not my mom. I don't think my mother did it to hurt me. Years later, she said while she drifted in and out of consciousness, she thought of me and called the medics.

And you want me to believe that all suicides are selfish? I don't think so.

We have a galling habit of judging people's pain because we don't have it. The addict doesn't understand the alcoholic, who doesn't understand the workaholic, who doesn't understand the gambler, who doesn't understand the obese, who doesn't understand the thief…

We pay endless lip service to tolerance, yet there's so little of it. If we don't suffer from said maladies, then no one should, and thus we perpetuate this cycle of ignorance, confusing illness for weakness. Junior Seau was in such soul-snatching pain that he took a gun to his chest and pulled the trigger. And rather than sympathize, we analyze with the objective hardness of a mortician.

My Dad, whatever else he is, was a man. And you don't dedicate your life to help another life unless you're selfless. And if you watched the blizzard of tears drip from the eyes of behemoths, men hardened by endless nights in the weight room who play a violent game with broken bones, men reared, taught, and trained on toughness, you'd see that Seau wasn't selfish, either. Selfishness is the domain of the demented, of someone who can only view the world through the warped prism of narcissism. That doesn't sound like Seau. And it definitely wasn't my Dad.

Seau left no note, and his last known communication was a text to his children, saying, "I love you." My Dad left me an identical message (via phone) before he tried to leave us. I don't doubt Seau's sincerity. Sometimes the pain trumps the gain.

When you're in hospice, or when a doctor gives you two months to live, and you decide that it's your time to depart and implore the doctor to pull the plug, we understand it, and even call it a "quality of life" issue. But when the pain is in the brain, we call you selfish and weak.

If your heart, lungs, or liver is harmed beyond repair, then your death at your behest is legitimized. But since we know so little about the brain, everyone becomes an amateur physician, meting out a medieval sense of medicine.

Sadly, Seau is not the first NFL player to take his own life, nor will he be the last. Indeed, a morbid montage is being painted with each year, results of savage head trauma. If you've followed the issue, you've seen scientists draw the haunting line between the constant collisions in football to protein buildup in the human brain, which can lead to depression, addiction, and suicide.

No matter how much padding we put in a man's helmet, we can't insulate him from concussions. And no matter how ardently you warn young men about the perils of a brain rattling inside a skull, the lure of fame, fortune, and women will invariably cloak the abstract notions of distant illness.

The reason many of us love sports – beyond the obvious, athletic splendor – is it doubles as a microcosm of the human condition, holding a wide mirror up to society. Former Chicago Bears safety Dave Duerson, like Seau, shot himself in the chest. Duerson was in too much agony to live but was coherent and caring enough to leave his brain intact.

Scientists studied it, and with each one we extract a lot more than protein and tissue. We find answers. And these answers can help other players, and other men. Maybe even my Dad.

Feel free to email me: Keidel.Jason@gmail.com