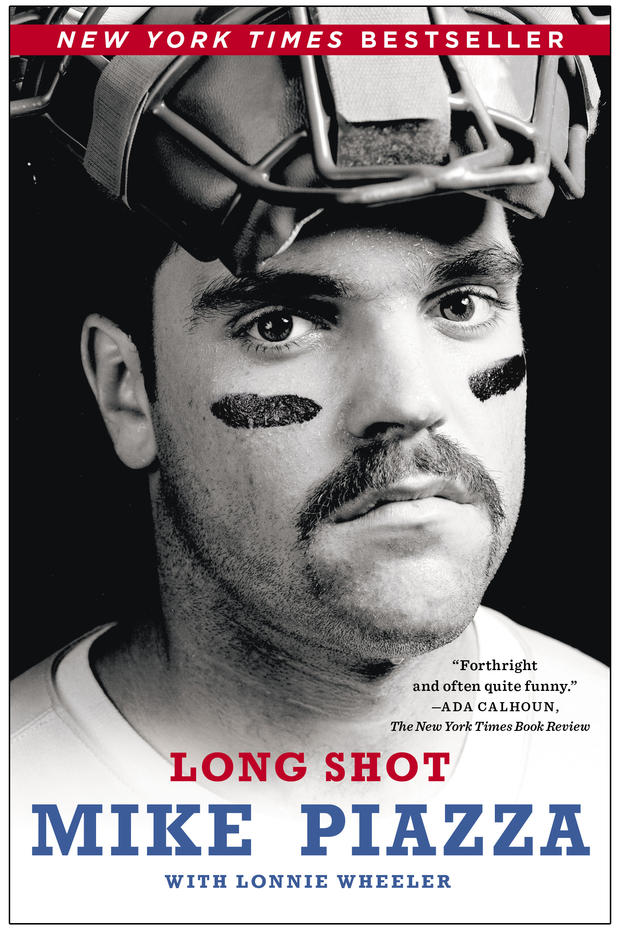

Mike Piazza's Memoir 'Long Shot' Chronicles His Career And Controversies

The second half of Piazza's career unfolded in New York City where he led the Mets to the 2000 World Series against the New York Yankees, quickly dubbed the "Subway Series." Piazza set the record for most home runs by a catcher at Shea Stadium, belting his 352nd to surpass Hall of Famer Carlton Fisk. More memorably, Piazza hit a home run at Shea in the first baseball game played following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. In this excerpt from LONG SHOT, Piazza talks about catching the final pitch at Shea during the stadium's closing ceremonies.

EXCERPT: The last game at Shea Stadium was held on September 28, 2008, against the Marlins. It was grim—the Mets' sixth defeat in their final nine games, during which time they fell out of first place (losing the division to the Phillies, who won thirteen of their last sixteen) and also squandered the wildcard (by one game to the Brewers, who won six of their last seven). I hate to say it, but it was typical Mets.

The closing ceremony was held after the game, which was a real mood killer. Other than that, it was a cool event. The festivities started Friday with a tribute to the greatest moments in Shea history. Number one was clinching the 1986 World Series, number three was clinching the 1969 World Series, and I slipped in between at number two, the home run to beat the Braves in the first game after 9/11. On Sunday, they laid out red carpets for the former players' entrances into the stadium. Tom Seaver and I were the last two to walk in. He came from left field and then I came from right, with my dad at my side. The fans were screaming my name, and of course my dad got emotional, which of course made me emotional. But I wouldn't have had it any other way. I felt strongly about giving back to my father, because, indisputably, he had been a tremendous inspiration in my career. He was a major reason why I was there.

Honestly, I sometimes felt as though I played more for my dad than I did for myself. But I didn't mind. I wanted to do it for him. The script had Seaver throwing the last pitch and me catching it. He was sixty-three years old, so I asked him if he wanted me to move up in front of the plate. "No, no, no," he said. Naturally, he bounced the ball to me. Ace defensive catcher that I was, I was able to snag it, even while nearly ripping my black dress slacks.

The whole affair felt good, and it spoke to why, if I do make it to the Hall of Fame—I'll be eligible for induction in 2013, along with Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Sammy Sosa, Craig Biggio, and Curt Schilling—I hope to go in as a Met. Technically, it's not the player's call; the Hall of Fame itself makes that decision. But players can let their preferences be known, and mine is pretty strong. Maybe I'm hypersensitive in this respect, but I appreciate appreciation. Over the years, the Mets have shown me theirs. I seldom felt that the Dodgers did.

In terms of pure baseball, the case for either team is not much different from that for the other. I hit more home runs (220-177) and drove in more runs (655-563) with the Mets, but had a higher batting average (.331-.296) with the Dodgers. I was Rookie of the Year with the Dodgers, but played more games (972-726) with the Mets. I went to the World Series with the Mets, but most of my best seasons (four of my top five finishes in the MVP voting) came with the Dodgers. Overall, largely because I suffered more injuries in New York and passed my prime there, I was probably a better player in Los Angeles, but the margin is not overwhelming. More important, performance is not entirely the point.

When I retired, Tommy Lasorda told USA Today, "I would hope he would go into the Hall of Fame as a Dodger. We're the one who gave him an opportunity." He's certainly right about that. Nobody else did, and the organization never let me forget it. It was a good deal for the Dodgers—a great deal—and yet, every time we negotiated a contract, they made me feel that I owed them. The last time, they turned the fans against me. Then they traded me. Ultimately, it was the Mets who gave me an opportunity. They also gave me the market-value contract that the Dodgers wouldn't. If there's a single person in my career with whom I feel most closely associated, yes, it's definitely Tommy. If there's a team, however, it's the Mets. In a hard-to-explain, total-picture sort of way—probably because of all that happened in those times, or maybe just because I'm an easterner—my years in New York represent real life to me. To that extent, the chief con-nection I felt was actually more with the fans and the city than the franchise itself, especially when my days as a Met were winding down. Two things, I believe, bonded me to Mets fans. The first was choosing to sign with the ball club after I was relentlessly booed in 1998. The main reason the people had given me a hard time in the first place was that they didn't believe I was committed to the organization. When they found out I was, it changed everything. The second factor was 9/11. It was a shared and profound experience, the kind that people can only get through together. Everyone suffered, and grew closer for it. That was still evident at the ten-year anniversary in 2011, held at Citi Field.

The anniversary was especially poignant. I caught the first pitch from Johnny Franco, with the infield ringed by first responders, representatives of Tuesday's Children (an organization dedicated to helping people affected by 9/11), and former teammates. It was a gratifying example of how, even after I'd left New York, Mets fans embraced me as one of their own. It didn't turn out that way in Los Angeles.

It's unfortunate that my relationship with the Dodgers had to end like it did. I wish I could look back on my first team and feel about it the way Carlton Fisk felt about his. He chose to go into the Hall of Fame wearing a Boston cap, even after the Red Sox cast him off. When his contract expired, they never even made an offer to keep him. Fisk eventually played longer with the White Sox, and had some of his better years in Chicago—I, for one, identify him more with the White Sox than the Red Sox—but when he retired, his heart was still with the franchise that brought him to the big leagues. Of course, my circumstances were a little different. Carlton turned thirty, played in the World Series, and went to most of his all-star games before changing colors. I did all of that with my third organization. Also, having grown up in New England, his feeling for Boston is obviously a little different, by nature, than mine is for Los Angeles. Even so, I can't say that I fully understand his decision. I don't have that inside me. I'd rather pull a Catfish Hunter. On his Hall of Fame plaque, the hat is blank, generic. To me, that's gutsy. That's integrity. If the Hall came to me and said, "We want you to go in as a Dodger," I'd say, "Well, then I'll go in as nothing." I just wouldn't feel comfortable with LA stamped on my head for all of eternity. Nah, if I'm fortunate enough to go to Cooperstown, it needs to be with New York of the National League. Seaver could use some company, anyhow.

Click here for Mike Piazza's LONG SHOT available now

LONG SHOT was released in trade paperback this month from Simon & Schuster, a division of CBS. This excerpt was reprinted with permission of the publisher. Copyright © 2013 by Catch 31, Inc. For more information on this or other newly released books, please visit our website: www.simonandschuster.com